Step into a darkroom from the 1800s, where pioneers of photography crafted images through an intricate dance of chemistry, light, and patience. These old photography techniques weren’t just methods of capturing moments—they were revolutionary acts that transformed how humanity preserved its memories.

From the ethereal beauty of daguerreotypes to the rich tones of albumen prints, each historical process tells a story of innovation and artistry. The inventors who developed these techniques weren’t just technicians; they were alchemists who turned silver nitrate, egg whites, and sunlight into permanent images that still captivate us today.

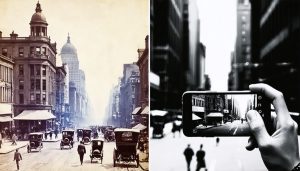

What’s particularly fascinating is how these centuries-old processes continue to influence modern photography. Contemporary artists are reviving techniques like wet plate collodion and cyanotypes, finding that these labor-intensive methods offer something that digital convenience cannot—a tangible connection to photography’s roots and unique aesthetic qualities impossible to replicate digitally.

Whether you’re a seasoned photographer or a curious newcomer, understanding these historical processes provides invaluable insights into the fundamental principles of photography. These techniques remind us that before Instagram filters and digital manipulation, photographers created stunning images through pure craftsmanship and deep understanding of photochemistry.

The Dawn of Photography: Early Pioneers

Daguerreotype: The First Commercial Success

Louis Daguerre revolutionized photography in 1839 with the introduction of the daguerreotype, marking a pivotal moment in historical photographic processes. This groundbreaking technique produced incredibly detailed images on silver-plated copper sheets, capturing the imagination of the public and establishing photography as a viable commercial medium.

The process involved treating a polished silver-copper plate with iodine vapor, creating a light-sensitive surface. After exposure in a camera, the plate was developed using mercury vapor and fixed with sodium thiosuflate, resulting in a unique, mirror-like image that appeared either positive or negative depending on viewing angle.

What made the daguerreotype truly revolutionary was its practicality. While earlier processes required hours of exposure, Daguerre’s method could capture an image in just minutes. This breakthrough made portrait photography accessible to the middle class, spawning a new industry of portrait studios across Europe and America.

Despite its popularity, the daguerreotype had limitations. Each image was unique and couldn’t be reproduced, making it impossible to create copies. The delicate surface required protective glass and specialized cases, and the mercury vapors used in processing posed serious health risks to photographers. Nevertheless, the daguerreotype dominated photography for nearly two decades, laying the foundation for all modern photographic techniques.

Calotype: Paper’s Revolutionary Role

In 1841, William Henry Fox Talbot introduced a groundbreaking photographic process that would revolutionize the medium: the calotype. Unlike the daguerreotype’s metal plates, Talbot’s invention used ordinary paper coated with silver chloride, making it both more affordable and practical for everyday use. The paper negative could produce multiple positive prints, marking the first time in history that photographs could be easily reproduced.

The process involved treating paper with silver nitrate and potassium iodide, creating a light-sensitive surface. After exposure in a camera, the paper negative was developed using gallic acid and fixed with sodium thiosulfate. The resulting negative could then be used to create positive prints through contact printing, where the negative was pressed against another sheet of sensitized paper and exposed to light.

What made the calotype particularly revolutionary was its aesthetic quality. The paper fibers created a slightly soft, atmospheric effect that many artists found appealing. While this meant that calotypes couldn’t match the sharp detail of daguerreotypes, they offered a more painterly quality that suited portraiture and landscape photography.

The calotype’s ability to produce multiple prints from a single negative laid the foundation for modern photography and the concept of image reproduction. This innovation would eventually lead to the development of more advanced negative-positive processes, establishing the basic principles that would define photography for generations to come.

Victorian Era Innovations

Wet Plate Collodion Process

The Wet Plate Collodion process, introduced by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, revolutionized photography by offering a perfect blend of image quality and practicality. This remarkable technique produced detailed images on glass plates and became the dominant photographic process during the American Civil War and Victorian era.

The process begins with a clean glass plate coated with collodion, a solution of gun cotton dissolved in ether and alcohol. The photographer then sensitizes the plate by dipping it in silver nitrate, creating light-sensitive silver iodide within the collodion layer. What makes this process unique is that the entire procedure – from coating to exposure to development – must be completed while the chemicals are still wet, typically within about 15 minutes.

Portrait photographers of the 1850s and 1860s particularly embraced the wet plate process because it offered shorter exposure times (typically 2-20 seconds) compared to earlier methods. This made it much more practical for capturing human subjects, though sitters still needed to remain perfectly still during exposure, leading to the characteristic stern expressions we associate with Victorian photography.

The resulting images, known as ambrotypes when produced on glass and tintypes when created on blackened metal, possessed extraordinary detail and a distinctive tonal range that modern photographers still admire. The process created rich, deep blacks and brilliant highlights, with a unique dimensional quality that seems to draw viewers into the image.

Despite its complexity and the need for portable darkrooms when shooting on location, the wet plate process remained popular until the 1880s. Today, a growing number of contemporary photographers are reviving this historical technique, attracted by its handcrafted nature and the unique aesthetic qualities it produces. The process requires careful attention to detail, precise timing, and a deep understanding of chemistry – challenges that many find creatively rewarding in our digital age.

Albumen Prints

The albumen print process, introduced in 1850 by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, revolutionized photography by producing images with unprecedented detail and subtle tonal gradations. At its core, this technique relied on an unlikely ingredient found in most kitchens: egg whites. The albumen from chicken eggs, when mixed with salt and coated on paper, created a smooth, glossy surface perfect for holding light-sensitive silver compounds.

To create an albumen print, photographers would separate egg whites from their yolks and whip them into a frothy mixture with salt. After allowing the foam to settle overnight, the resulting liquid would be carefully coated onto fine paper. Once dry, this paper was sensitized with silver nitrate, creating a light-sensitive surface that could capture images with remarkable clarity.

The process became the dominant photographic printing method of the Victorian era, accounting for roughly 85% of all photographs produced between 1855 and 1895. Cartes de visite and cabinet cards, the popular portrait formats of the time, predominantly used albumen prints. The technique’s success stemmed from its ability to produce rich, warm tones and sharp details that previous processes couldn’t achieve.

What made albumen prints truly special was their distinctive surface sheen and the way they rendered subtle highlights and shadows. The egg white coating created a semi-glossy surface that enhanced the image’s three-dimensional appearance, making portraits appear more lifelike than ever before. However, the process was labor-intensive – a single batch of solution required dozens of eggs, and the coating process demanded considerable skill and patience.

Today, while no longer used for commercial photography, albumen printing continues to fascinate alternative process photographers and artists who appreciate its unique aesthetic qualities and historical significance. The distinctive yellowish tinge and subtle surface texture of albumen prints remain instantly recognizable to photography collectors and historians.

Early Color Processes

Autochrome Lumière

The Autochrome Lumière process, introduced in 1907 by the Lumière brothers, marked a revolutionary breakthrough as the first commercially successful color photography method. This ingenious technique used millions of tiny dyed potato starch grains acting as color filters, creating stunning color images that captured the world in vivid detail for the first time.

The process involved coating a glass plate with a layer of potato starch grains dyed in orange-red, green, and violet-blue. These microscopic grains were combined with carbon black powder to fill the spaces between them, creating a mosaic color filter. A silver bromide emulsion was then applied over this layer, resulting in a unique color-sensitive plate.

When photographers exposed these plates, light would pass through the colored starch grains before reaching the emulsion, effectively filtering the colors of the scene. After processing, the plate produced a positive image that showed natural colors when viewed by transmitted light. While the exposure times were quite long – often several seconds even in bright sunlight – the results were remarkably beautiful, with a distinctive soft, dreamy quality that many modern photographers still try to emulate.

The Autochrome process remained popular until the 1930s when newer, more practical color film processes emerged. Today, original Autochrome plates are highly valued for their unique aesthetic and historical significance, offering a rare glimpse into the colorful world of the early 20th century.

Early Color Film Development

The journey toward color photography began in the 1850s with the first experiments in capturing the full spectrum of visible light. James Clerk Maxwell made history in 1861 by creating the first color photograph, using three separate black-and-white images taken through red, green, and blue filters. These images were then projected together using colored lights to produce a single color image.

A significant breakthrough came in 1907 when Auguste and Louis Lumière introduced the Autochrome Lumière process, the first commercially successful color photography method. This innovative technique used microscopic potato starch grains dyed in different colors to create a color filter array, producing dreamy, pointillist-like images that captivated the public.

The next major advancement arrived in 1935 when Kodak introduced Kodachrome film, revolutionizing color photography. Kodachrome used a complex development process that produced incredibly stable, vibrant colors that could last for decades. This was followed by Agfacolor in 1936 and Ektachrome in 1940, each offering different approaches to color capture and processing.

These early innovations laid the groundwork for modern color photography, though they were often expensive and complex to use. Professional photographers needed specialized knowledge and equipment, while amateur photographers had to rely on photo labs for processing. Despite these challenges, these pioneering technologies paved the way for the digital color imaging we take for granted today.

Modern Revival and Artistic Applications

Alternative Process Movement

In recent years, there’s been a remarkable resurgence of historical photographic processes among contemporary artists seeking to blend traditional craftsmanship with modern artistic vision. These artists are exploring creative photography techniques that harken back to photography’s roots while adding their unique contemporary perspectives.

Notable practitioners like Sally Mann have embraced the wet plate collodion process, creating haunting portraits and landscapes that showcase the distinctive aesthetic of 19th-century photography. Mann’s work demonstrates how historical techniques can convey powerful emotional depth in modern contexts.

Similarly, photographer Joni Sternbach has gained recognition for her tintype portraits of surfers, combining a Victorian-era process with contemporary subject matter. Her work exemplifies how historical methods can bring fresh perspectives to modern subjects.

The alternative process movement has also found its way into fine art galleries and museums, with artists like France Scully Osterman and Mark Osterman teaching workshops to preserve these traditional methods. Their dedication helps ensure these techniques aren’t lost to time.

Many practitioners appreciate how these historical processes require careful attention to detail and hands-on craftsmanship, offering a refreshing departure from digital photography’s instant gratification. This movement continues to grow, inspiring new generations to explore photography’s rich technical heritage while creating distinctly modern works.

Digital Meets Vintage

In today’s digital age, photographers are discovering innovative ways to blend historical processes with modern technology, creating unique artistic expressions that bridge centuries of photographic evolution. This fusion of old and new has given rise to a renaissance in alternative process photography, where artists combine digital negatives with traditional printing methods.

Using modern inkjet printers, photographers can create large-format digital negatives specifically designed for historical processes like cyanotypes, platinum prints, or wet plate collodion. These digital negatives offer unprecedented control over contrast, density, and detail while maintaining the authentic charm of vintage processes.

Software tools now exist that help photographers optimize their digital files specifically for alternative processes, allowing for precise adjustments that would have been impossible in the traditional darkroom. Mobile apps even enable photographers to preview how their digital images might look when printed using various historical techniques.

Some contemporary artists scan their wet plate collodion images to create hybrid works that showcase both the distinctive characteristics of 19th-century photography and the flexibility of digital manipulation. This marriage of technologies not only preserves traditional craftsmanship but also opens new creative possibilities, allowing photographers to express their artistic vision through a unique combination of historical and contemporary methods.

The enduring legacy of historical photographic processes continues to influence and inspire photographers in the digital age. While modern photography techniques have made image-making more accessible and efficient, many contemporary artists are returning to these time-honored methods to create unique and compelling works.

These historical processes offer more than just nostalgic appeal; they provide photographers with distinctive aesthetic qualities that cannot be fully replicated through digital means. The rich tones of albumen prints, the ethereal quality of cyanotypes, and the dimensional depth of daguerreotypes continue to captivate viewers and creators alike.

The revival of these traditional techniques has sparked a renewed appreciation for the craft of photography. Workshops, specialized studios, and educational programs dedicated to historical processes are flourishing worldwide, creating communities of practitioners who keep these arts alive. This renaissance has also influenced digital photography, with many editing tools and filters attempting to recreate the characteristic looks of these early processes.

Perhaps most importantly, these historical methods remind us of photography’s fundamental nature as both an art and a science. They teach us patience, precision, and the value of hands-on craftsmanship in an increasingly automated world. By understanding and practicing these traditional techniques, photographers gain a deeper appreciation for their medium’s evolution and the countless possibilities that still exist for creative expression.

As we continue to advance technologically, these historical processes serve as both a bridge to our past and a source of endless inspiration for future innovations in photography.